On jellyfish and federal funding

A lot has been made the past few weeks about various snubs by the Nobel Foundation in choosing the 2008 Nobel Prize recipients. The one that's received the most play in the media has been the Nobel in physiology/medicine, which went to two French scientists who isolated HIV in the 1980s. The prize didn't include Robert Gallo, an American scientist who linked HIV to AIDS.

Scientific American has an interesting list of 10 scientists who probably should've received Nobel prizes ... but didn't. (One fault is that the Nobel specifies that it can only be shared by three researchers, so everyone else loses out.) But the list doesn't mention Douglas Prasher, who probably should've had a hand in the 2008 Nobel Prize for chemistry.

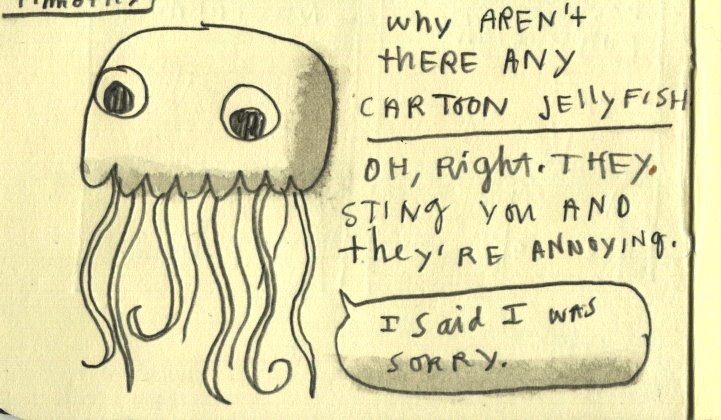

Truth is, there's been relatively little media play over Prasher. The 30-second version: Dr. Prasher discovered a gene that makes jellyfish glow and believed the discovery could be used in detecting cancer and other diseases. Then his funding ran out. In an last-ditch effort to save his research, he sent test tubes with the gene to two other scientists. They continued his work and won the Nobel. He won nothing. (They have, however, conceded he made a vital contribution to the findings.) But here's the rub: While the winning scientists are sharing a $1.5 million prize, Prasher is driving a courtesy shuttle for an Alabama Toyota dealership. He makes $8 an hour. (CNET has a longer, well-written story if you're so inclined to read more.)

Truth is, there's been relatively little media play over Prasher. The 30-second version: Dr. Prasher discovered a gene that makes jellyfish glow and believed the discovery could be used in detecting cancer and other diseases. Then his funding ran out. In an last-ditch effort to save his research, he sent test tubes with the gene to two other scientists. They continued his work and won the Nobel. He won nothing. (They have, however, conceded he made a vital contribution to the findings.) But here's the rub: While the winning scientists are sharing a $1.5 million prize, Prasher is driving a courtesy shuttle for an Alabama Toyota dealership. He makes $8 an hour. (CNET has a longer, well-written story if you're so inclined to read more.)I think every scientist fears what happens when the funding dries up. I mean, everybody worries about how they'd pay the bills if they lost their jobs. (And boy, does it ever sting. Don't get me started about how hard it's been looking for a job in this economy, where job-seekers outnumber jobs three to one.) But scientists face a special kind of job insecurity. A lot of funding comes, in one form or another, from the government. And that means campaign-happy terms such as "spending freeze" can be scary. Something to think about during election season.

But back to Prasher. I don't know what I would've done had I been in his shoes. Would I have sent my research on or selfishly kept it for myself? Probably neither. Instead, I probably would've assumed my research wasn't really that good -- otherwise, wouldn't somebody want to pay for it? -- and quietly packed up my beakers and notebooks.

There's something to be said for Prasher's confidence in his work. He knew a good thing when he saw it. Unfortunately, the dollars don't always go where they should. In a perfect world, he'd see some of that Nobel cash. But even if he doesn't, here's hoping somebody recognizes he should be in a lab instead of behind the wheel of a Toyota courtesy shuttle.

Bonus link: "Obama, McCain Battle for Science Cred" (AP, Oct. 16)

2 Comments:

Kate,

If you had read And the Band Played On in 1985, as I did, you would have no pity for Dr. Gallo. Perhaps he's mellowed with age. He is probably the darkest character that Alan Alda has ever played (in the movie of the same book). I think if you look into it, you'll find the Nobel committee called that one right.

As far as scientists go facing a special kind of job security.

It's worth pointing out that it sounds like Dr. Prasher was essentially on soft-money. Money tied to grants as post-doctoral researchers or as senior research scientists.

Typically - that funding works such that you are budgeted for a certain amount of time - usually yearly contracts - then you try to keep the funding rolling to stay wherever you are at. Or get money to go elsewhere.

Then there is hard money - tenure track positions where Institutions essentially make an investment and hope that you bring in more money than you cost thereby making the cash monies.

I chose the hard-money route. I could have gone off to do a post-doc, but honestly - in this funding environment where the NSF is funding right around the 20% level - why put myself through that kind of stress. That 20% level means that only 1 in 5 researchers who apply for funding get it. And thats just the NSF, the NIH is in a similar situation.

Basically - the big granting institutions are cash-strapped in terms of funding which makes it hard on everyone. Unfortunately, the people who really get screwed by this are the soft-money scientists and the tenure-track professors who are trying to get external funding - but having a very difficult time - who then get frustrated with the process and go "fuck it". (Note - That is not me yet).

The most soul-crushing part is knowing you STILL have to write proposals, even though it can be pretty futile, because if you don't - you aren't bringing in the cash-monies - thus less likely to get tenure.

My understanding is that the funding situation was not so bad in the 80s and 90s, where there was a much better shot at getting funding and thus being considered successful.

Also - i would like to point out that doing research with funding is waaaaaay more fun and satisfying than trying to do it without funding and having to beg/convince people to give/loan you stuff so you can do things.

Post a Comment

<< Home